As much of the country hunkered down against storms that threatened to bring a month of rain in one day, us poets gathered to take a little stroll around London (inspired by the Formerly exhibition at the Poetry Café). Our meeting point was outside Chancery Lane tube, at the dragons marking the boundary of the City. We arrived armed with umbrellas and waterproofs, but at half past ten, our official starting time, the sun crept from between two large grey clouds, and we could see patches of blue sky in the middle distance. As I said to the group, we don’t want the weather to be too cheerful, because our walk would take in the dark and clammy corners of the area that lies between Clerkenwell and Bloomsbury, an area I have always thought of as the Fleet Valley.

Many years ago, around the time I lived in North Mews, a cobbled street running parallel with the Grays Inn Road, I picked up a book at a second-hand stall entitled The Lost Rivers of London by Nicholas Barton. The subtitle of the book was ‘A study of their effects upon London and Londoners, and the effects of London and Londoners upon them’. The subtitle was important, I discovered, as the book wasn’t so much a history of the rivers as an essential guidebook to a hidden underworld. It wasn’t until much later that I came across the phrase genius loci, which describes the spirit of a place which is made manifest through a sense of the histories of its previous inhabitants and its notable events. It explained the odd sensation I had when I lived in that neighbourhood of something I couldn’t quite place, unsettling and sinister. It was during my time in North Mews when I wrote this poem:

Fleet

It flows beneath my feet, its subterranean banks

unseen. I glide blissfully through my day,

all liquid, like a fish. I can’t understand

what gives this extra lift to my step, as if I’m floating,

and the cars drifting through Clerkenwell Green

are barges carrying sailors home from sea.

But an undercurrent sinks me at Islington:

I sense the bones of the old prison, the plague-dead

dumped straight from their beds, butchers’ scraps

staining the water blood red. The old dark brick

shifts, the city groans in its foundations

and spits me out like a sour grape into the street.

As we made our way through Leather Lane, up Saffron Hill, once the most notorious rookery in London (and the dirtiest and most wretched place that Dickens could think to situate Fagin and his den of thieves), across the Clerkenwell Road, and over Herbal Hill, I think we could all sense the river below us. Peter Ackroyd describes the Fleet as ‘London in essence’, plague-ridden and treacherous, but legendary, the tributary of all that was wild and radical in London. We found a plaque at the bottom of Herbal Hill, undated, but marking the moment the river officially became a sewer.

Outside the Coach and Horses, famed in its day for prize-fights with every conceivable weapon, cockfighting, bull-baiting and bear-baiting (which led to the death of the landlord in 1709), we stood in the middle of the road and peered down into a grate where we could hear the low swoosh of water, the only true vestige of the Fleet, still flowing fast below.

We were standing in the middle of the river, in what was once Hockley-in-the-Hole, an area of street crime and gangs, where women were attacked and stuffed in empty beer barrels and rolled down the hill. We passed under the bridge that carried Rosebery Avenue above our heads, to the inappropriately-named Mount Pleasant, and the huge, ugly Royal Mail Sorting Office that was once the site of Cold Bath Prison (to Coleridge, the site of Hell). We took in the moumental car park, the last undeveloped Second World War bomb site in central London, resplendent with weeds and garbage.

After that, we headed towards Dickens’ House, down Rugby Street (past number 18, where Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes consummated their relationship), over to pay a visit to Charlie Dutton in his gallery on Princeton Street, through Red Lion Square (past the house where Rossetti first painted Lizzie Siddal, and his new flatmate, William Morris, knocked up a few bits of furniture for their bedsit) and on to the Poetry Café for lunch and time to write some poems. But not before we stopped at the corner of Kingsway and Parker Street, the site of Charles Lamb’s lodgings in 1801. It was from there he wrote to Wordsworth:

Separate from the pleasure of your company, I don’t much care if I never see a mountain in my life. I have passed all my days in London, until I have formed as many and intense local attachments as any of you mountaineers can have done with dead Nature. The lighted shops of the Strand and Fleet Street; the innumerable trades, tradesmen, and customers, coaches, wagons, playhouses; all the bustle and wickedness round about Covent Garden; the very women of the Town; the watchmen, drunken scenes, rattles; life awake, if you awake, at all hours of the night; the impossibility of being dull in Fleet Street; the crowds, the very dirt and mud, the sun shining upon houses and pavements, the print shops, the old bookstalls, parsons cheapening books, coffee-houses, steams of soups from kitchens, the pantomimes - London itself a pantomime and a masquerade - all these things work themselves into my mind, and feed me, without a power of satiating me. The wonder of these sights impels me into night-walks about her crowded streets, and I often shed tears in the motley Strand from fullness of joy at so much life.

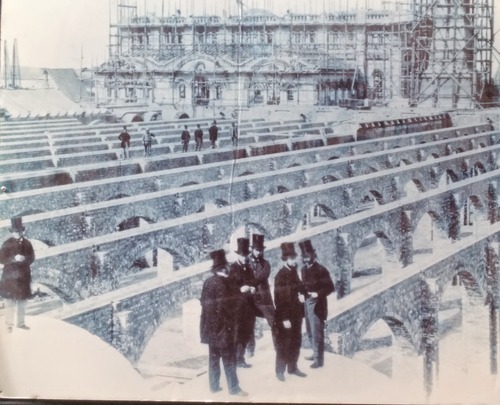

The photographs were taken by Vici MacDonald, my collaborator on the Formerly project. The exhibition continues at the Poetry Café through August. The book can be ordered here: http://herculeseditions.wordpress.com/