Continuing my series on art in lockdown, considering the pictures on my walls.

I’ve written here on Prunella Clough ten years ago; she died eleven years before that – but her strange, bleak imagery still feels startlingly modern. No one else was making work like hers in midcentury Britain, balanced somewhere between figurative and abstract, often informed by urban settings but also by inner vistas. There are five of Clough’s works on paper in this house; each one is distinctive, beautiful in a sullen way.

With Clough, a flower wasn’t something romantic or sentimental, it was tough – like her Black Peony (Paper Flower), a lithograph from the mid-80s. The flowerhead is shut, like a fist, thrusting on its thin stem through the tangle of foliage around it. The ‘paper’ of the subtitle references the material the image is printed on, but also hints at the Latin name, Papaver (from the poppy family) Somniferum (literally ‘sleep bringing’). This is a narcotic, an opium poppy, slowly rising its dreamy head through a haze in which it almost disappears – the way you might in a dream, or in a cloud of smoke.

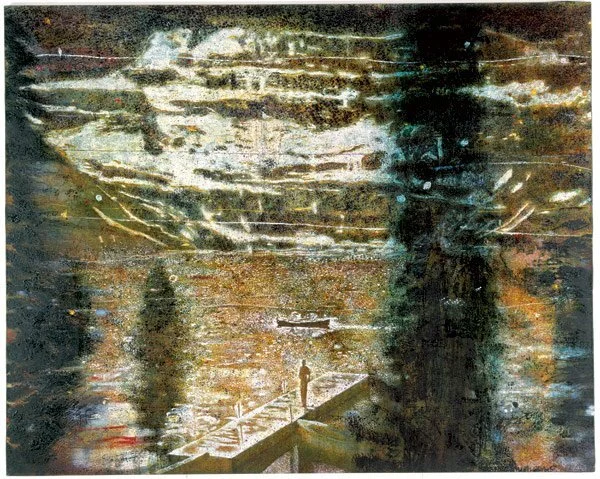

Delphic, Prunella Clough, 1996

Her imagery is like that sometimes – dreamlike, hard to pin down. Delphic means ‘obscure’ and ‘ambiguous’. In her screenprint of the same title, made for the Freud Museum in 1996, a black mass with a pointed peak fills a neutral space like an inscrutable mountain. Is this the cloak of the Oracle on a ceremonial tripod, or a temple flame burning on a pyre (a reddish fire emits from the right side of the mass)? Is Freud the Oracle to be consulted? Freud was acutely interested in the classical world and crowded his famous study with artefacts from Greek and Roman culture. There is something totemic and solid about Clough’s image, but also frightening. If this is a dream, it is a nightmare.

Prunella Clough, Bubble Wrap, 1993

Clough was fascinated by the architecture of things. Bubble Wrap is a lithograph from 1993 – a playful exploration of an ordinary packing material (the thing the picture is typically wrapped in rather than the star of the show) employed for its ability to create pattern. The choice of green suggests something plant-like – there is often a tension between the manmade and the natural world in Clough’s work. She’s not interested in perfection; she makes a tear that drives through the centre of these circular shapes (which to me look like fingerprints). With Clough, the abstract is in the objects around us – we just need to look closely to find it.

What do I get from staring at her images on my walls? They are endlessly mysterious, uncanny (going back to Freud), their meaning remains unfixed, no matter how long I’ve lived with them around me. They have a particular kind of quiet drama, which is the same quality I look for in a poem (I don’t know if Clough liked Wallace Stevens, but I find affinities between them). I thought of her the other day when I saw a discarded surgical mask on the pavement – I could see her making something of that, indeed of this whole pandemic with its enforced isolation, its hidden virus.