Having recently visited the newly-reopened William Morris Gallery, I’ve been thinking a lot about Morris’s ethos for domestic life: have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful. In his time, a feather duster had real feathers and a turned wooden handle. You can still get proper feather dusters in shops like Labour and Wait and Objects of Use, which make fetish items out of common domestic tools. These dusters are expensive; you wouldn’t want to use them to dust. But they make the point that we don’t often step back and look at the ordinary everyday objects around us, and if we do, we probably would agree on the subject of their usefulness, but seldom on their beauty.

The Victorians believed in the ethos of beauty, to the point that they erected beautiful hospitals and prisons, lavishly landscaped cemeteries. Even sewage plants.

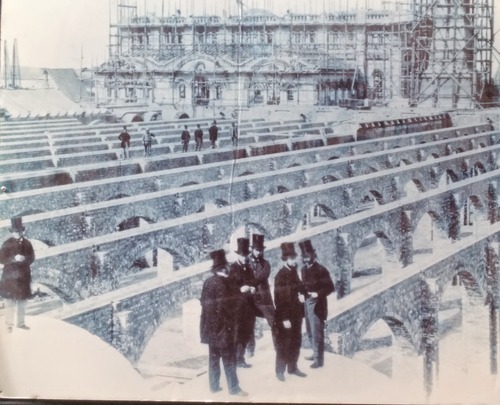

The Crossness Pumping Station was designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette and opened with great fanfare by the Prince of Wales in 1865. It is a stunning Italianate building – not quite as impressive from the outside as Abbey Mills, which was known as the Cathedral of the Sewers – but inside it has some of the most intricate and stunning Victorian cast ironwork I’ve ever seen. It still holds the four original pumping engines, possibly the largest rotating beam engines in the world, with 52 ton flywheels and 47 ton beams. It is in the process of being lovingly restored.

As we walked along the river, we came across more ruins of London’s industrial past. The stretch between Crossness and Erith can only be described as bleak, a truly dystopian landscape. Some factories are still running, their giant plants humming and belching. Disused jetties extended into the river then came to an abrupt end. Cormorants fought over the fish that swim into the warm waters created by the factory overflow.

We reached Erith late afternoon. The sun was still shining brightly on the concrete and rust. Although you wouldn’t know it to look at the place now, Erith had a grand history. It was established in Medieval times, an important religious centre and a port. Henry VIII decided to open a naval dockyard there.

No one could claim it is beautiful. But there is something impressive about a place that refuses to die, that still gives a home to the most wild and unkempt nature. It is not a destination, but it has its own strange interest. And there is always the river, a sludgy brackish brown in this stretch, but wider here, where it passes under the Dartford Crossing. We felt as if we were leaving London on foot. At Erith, we came off the path and found our way to the station, to head back to the tamer quarters of the city.