OK, so it’s not everyone’s idea of an exotic mid-week break, and indeed, I was met with sniggers from a few friends when I mentioned I was off for a jaunt around Birmingham with Vici. I trust Vici implicitly when it comes to cities, as she is the great connoisseur of all things urban – and she is a fan of Birmingham. Besides, I’d never been, and in my nearly-thirty years of living in the UK, I’ve managed to visit most of the other major English cities. It seemed odd that the one I’d missed is actually closest to London, only an hour and a half by train.

I’ve always been attracted to ‘second’ cities (Antwerp is a good example – to my mind, far more interesting than Brussels). Their charms are not as obvious as in the grander capitals, but they are often edgier, friendlier, their architecture more challenging or unusual, their history more evident (in that they haven’t had the finance or the opportunity to modernise or ‘sanitise’ their public spaces). They are easier to explore, or at least smaller – coming from the great sprawl of London, I appreciate going to a city centre that fits on a single map.

But Birmingham gets a bad press. Perhaps

it’s down to its architectural history – some of the great (or terrible,

depending on your view) statements of brutalism have been erected there. The

Bullring is now a swanky shopping precinct, but in the seventies it was

notorious, the unfriendly face of urban planning. Even its name suggested

somewhere alien, thuggish and claustrophobic. What remains is the glorious Rotunda,

Birmingham’s diminutive version of the Shard – visible from just about anywhere

in the city; from the top floor it offers an incredible panoramic view.

Often second cities retain the character that gets swept away in gentrification. Small industry has all but vanished from the centre of London. I remember when I was eight or nine travelling with my father through the darkened industrial spaces of Tooley Street, where there were still warehouses and printers, and how properly Dickensian it felt to an American child – and exciting. Those warehouses eventually made way for large-scale tourist attractions, such as the London Dungeon, and Tooley Street is now like most other roads in London, serving the consumer industry with the usual burger restaurants and beauty salons, and branches of Tesco and M&S.

But as we wandered through Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, you could hear the rush and whirr of

machines making the pieces for sale in the area’s shops. These were real,

operational factories, unlike the factory buildings of the Docklands and

Shoreditch, now all luxury apartments. Gentrification is creeping here too, but

it still feels like the place has managed to hold onto much of what makes it interesting.

I was reminded of Roy Fisher, Birmingham’s unofficial laureate, whose poems are both robust and beautiful at the same time. Fisher says of Birmingham that it’s a ‘nowhere’ as far as the rest of England is concerned, that ‘no-account bit in the middle’. Fisher talks about the city, in all its nondescriptness, as a place which wasn’t spoken about or written about when he was first becoming a poet. I’ve quoted Fisher here before, as he is, to my mind, a poet who writes about the urban experience like no one else. When he was writing his epic, ‘City’, Birmingham was in flux. But I can still feel the pull of the old as I walk over the cobbled streets of the Jewellery Quarter. Fisher writes:

Brick dust in sunlight. That is what I see now in the city, a dry epic flavour, whose air is human breath. A place of lines made straight with plumbline and trowel, to desiccate and crumble in the sun and smoke. Blistered paint on cisterns and girders, cracking to show the priming. Old men spit on the paving slabs, little boys urinate; and the sun dries it as it dries out patches of damp on plaster facings to leave misshapen stains. I look for things here that make old men and dead men seem young. Things which have escaped, the landscapes of many childhoods.

Wharves,

the oldest parts of factories, tarred gable ends rearing to take the sun over

lower roofs. Soot, sunlight, brick-dust; and the breath that tastes of them.

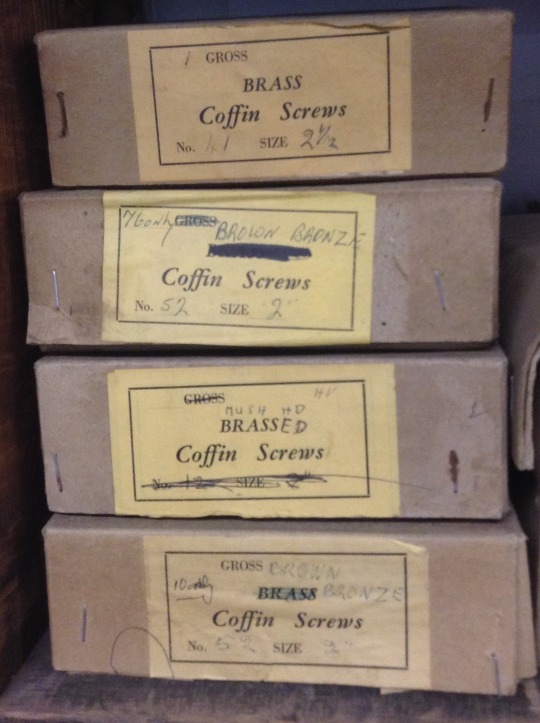

How amazing then to find a place like the

Coffin Works, a museum dedicated to the history of Newman Brothers Coffin

Furnishers, the last of a dozen coffin manufacturers to operate in the city (it

closed its doors in 1999). It’s an extraordinary feat of preservation, a love

song to a livelihood now finished, and to a way of commemoration which has also

passed.

Two exhibitions around town emphasised the

idea of memorialising / manufacturing. Fiona

Banner’s glass scaffold at Ikon is also a ghost, something that exists and

doesn’t, to paraphrase the artist. It suggests construction, but is nearly

invisible, so that we think of how things are built, but we stand in a gallery

that seems empty – we can see through the glass, into both the present of what

is made (the glass is transparent, but still solid) and the past of the empty

room.

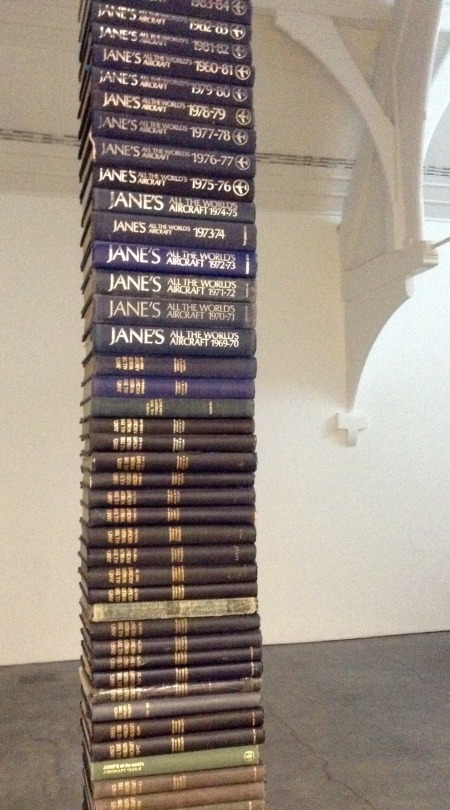

Banner is also interested in cataloguing and assembling, and so her

entire collection of Jane’s All the World’s

Aircraft is stacked to form a column in the middle of the gallery, a precarious

tower.

At mac, the filmmaker Atom Egoyan has installed

Steenbeckett, a paean to celluloid.

Two thousand feet of 35mm film is spooled and looped through pulleys around a

darkened gallery, powered by an old Steenbeck editing machine. The film is Krapp’s Last Tape, in which Egoyan

directed John Hurt. We can hear his disembodied voice through the noise of the reels

passing through their elaborate mechanics. In another room is Krapp’s table,

where he sits processing his box of recordings. There is something beautiful in

the dusty technology, pre-smart phone. The ghostly echo of analogue.

In his monologue, Krapp talks about ‘those things worth having when all the dust has – when all my dust has settled’ and I think again of Fisher’s ‘brick dust in sunlight.’