On the final Saturday in September, as the last rays of summer sun shone on London, a group of poets, artists and designers spent the day on the trail of William Blake, in the company of our brilliant guides, Sophie Herxheimer (http://sophieherxheimer.com/) and Chris McCabe (http://chris-mccabe.blogspot.co.uk/).

This is familiar territory, explored here before http://invectiveagainstswans.tumblr.com/post/24683335676/number-13-hercules-buildings-lambeth . I walk past the site of Blake’s house in Hercules Road at least once a week, and I have even named my little press after that address. Indeed, I’ve been resident in Blake’s patch, first across the park in Southwark, then in Lambeth itself, for 17 years. There is something about the cosmic pull of south – as Chris pointed out during our walk, it was (and in some ways still is) a place of non-conformity, raising a fist towards Parliament across the river. It was the location of circuses and pleasure gardens, music halls and ale houses, ‘seedy pleasures’, as Stanley Gardner has described them.

We started, of course, where Blake’s house at Number 13 Hercules Buildings once stood – and Sophie told us something I didn’t know (no matter how long I live in London, there is always something new to know). She mentioned a strong man in Philip Astley’s circus named Hercules (Astley’s mansion, Hercules Hall, was down the road from Blake’s house). Doing a bit of Googling, I found the site of Astley’s Ampitheatre on Westminster Bridge Road https://londonstreetviews.wordpress.com/2013/04/25/astleys-royal-amphitheatre/. The site also tells us that the ‘strong man’ in question was Andrew Ducrow, originally from Belgium, who was able to lift a table with four or five children on it with his teeth. His nickname was ‘The Flemish Hercules’. Ducrow is a familiar name to me, as his grave is one of the most spectacular in Kensal Green Cemetery, more circus ring than mausoleum.

Chris McCabe will be hitting Kensal Green in his long-term project to find the lost poets buried in the ‘magnificent seven’ Victorian cemeteries of London. This is a link to his first instalment, the product of his exploration of West Norwood http://www.pennedinthemargins.co.uk/index.php/2014/05/in-the-catacombs-a-summer-among-the-dead-poets-of-west-norwood-cemetery/

But back to Lambeth. We crossed Hercules Road, past the horrible new Crown Plaza hotel that has risen like one of Blake’s terrible serpents and now dominates the block opposite. It was this (and a drawing by Alison Gill, a constructivist composition of cranes and scaffolding) that prompted my poem, recently featured in Tom Bland’s online journal Blue of Noon

http://blueofnoonpoetry.tumblr.com/post/147744704015/the-lambeth-prophecy

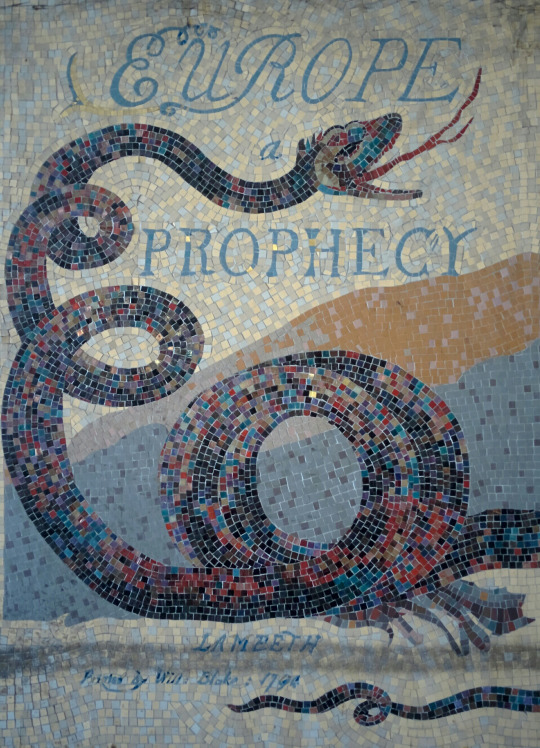

We proceeded down Centaur Street and then Virgil Street – a grimy, dirty conflation of streets running off Hercules Road under the railway line, dotted with pigeon excrement and graffiti. But also, for those who take the trouble to seek them out, some stunning mosaics based on Blake’s illustrations.

We walked up to Lambeth Palace, and along the river to Westminster Bridge, then back to Vauxhall, finally ending up in the Blake room in the Tate. During the day, Sophie asked us to find the ‘textures’ of London, rough and smooth. Chris asked us to find our ‘own William Blake’ in the landscape. And suddenly, everywhere, there were poems in trees and signs and pavements.

For me, one of Blake’s most moving statements about London is his poem of the same name, which was written while he was resident in Hercules Road. During our session, we discussed Blake’s use of the word “chartered”, a term from banking and business, which still feels modern in the age of property deals (I know exactly what Blake would think of the hotel taking over the end of his road …). It begs the questions ‘Who owns the streets’? ‘What rights do we have as city dwellers?’ Blake’s insistence on ‘every’ in the second stanza shows that in his London, everyone is a stakeholder, from man to child, but the stanza resolves itself by having them all in chains. The churches are blackened, from the chimneys of new factories belching out smoke, and the palaces have blood running down their walls, from the deaths of soldiers called to fight in the French Wars. And the human drama continues: the harlot’s ‘curse’ is passed to her child, and to her client, who takes it into his marriage bed, or ‘marriage hearse’, suggesting that what they all face is an early death. The Harlot represents innocence ‘blackened’, like the chimney sweep in the previous stanza. It’s a microcosm of his London, which puts me in mind of Hogarth, who, although a very different kind of artist, shared Blake’s concern for the London poor.

While on our walk, the news flashed over our phones that Jeremy Corbyn has secured the Labour leadership. I wonder what Blake would have said …

London

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear

How the Chimney-sweepers cry

Every blackning Church appalls,

And the hapless Soldiers sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls

But most thro’ midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlots curse

Blasts the new-born Infants tear

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.