After my father died in 2007, I put what was left of his library in storage. It’s hard to say how many books he’d had originally, maybe 10,000. He started his career as a publisher when he was in his early thirties, and so the books he’d seen into the world formed a large part of the collection, as well as books from fellow publishers, authors who were also friends, books on subjects that interested him – American history, philosophy, literature, Judaica. When I was a child, I used to spend hours in the room that contained his library. It was separated from the main body of the house by a glass patio – as a result, it was always a few degrees colder than in the rest of the house. That cold air has stayed with me, as if each time I open a book, it gives off a puff of breeze to wake me up.

I find it difficult now to remember other rooms in my childhood house – I must have spent more time in the kitchen, which was at the other end of the patio, but I can’t recall much about it, apart from a hazy notion of its layout. But I can picture the library as if I’d just left it, even the smell. Gaston Bachelard says:

We comfort ourselves by reliving memories of protection. Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images. Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling these memories, we add to our store of dreams; we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.

I took that idea of my father’s library as a protecting space, cut off from the rest of the house, as a image to begin this poem:

The Library

The fire was never lit. Cold, her body

was alert to words, her pores open to knowledge.

Sealed off from the rest of the house, padded

with paper and board, the only sound was the turning

of the page, a whisper, her shallow breath.

Gone. The books scattered to far corners,

cities a thousand miles away, strange

against paperbacks with rainbow covers,

they still carry the scent of deerskin and beeswax,

mildew—travellers from an antique land.

The model ship that used to drift the dark oak desk

is lost, never to reach the new world,

never to return home. She would touch

its windless sails, wonder at how they could make

everything so small. A planet reduced.

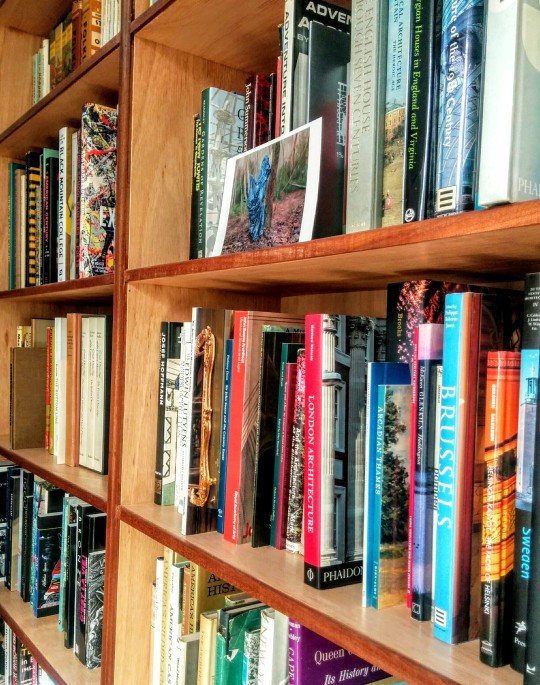

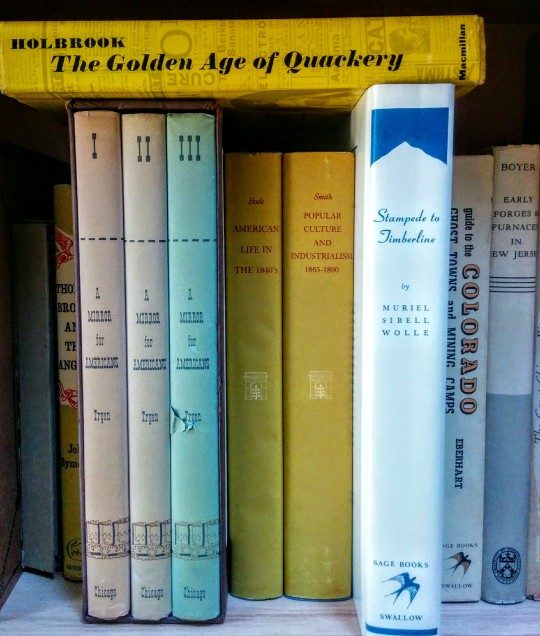

As my parents downsized, so did the library’s holdings. Finally the last two thousand or so books were boxed and removed from my mother’s house in West Windsor, her final US address before she moved to London, where she lived for her remaining five years. After navigating the Atlantic, the books landed in a warehouse in Bury St Edmunds, in huge crates (I went to visit them once in situ, and was reminded of the final scene in Citizen Kane). And now they have found a new home, mingling with their much younger companions – the books I’ve assembled over the years.

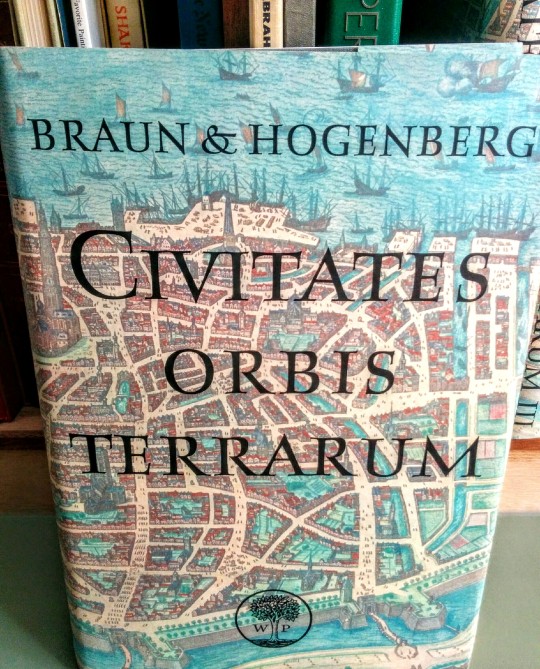

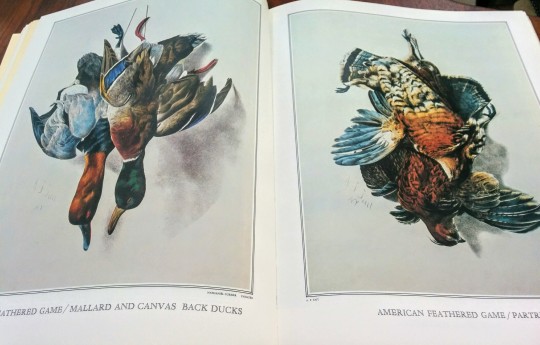

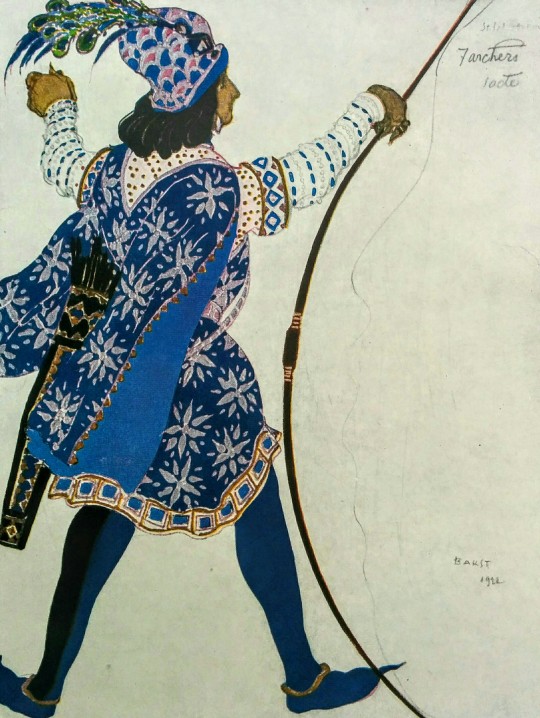

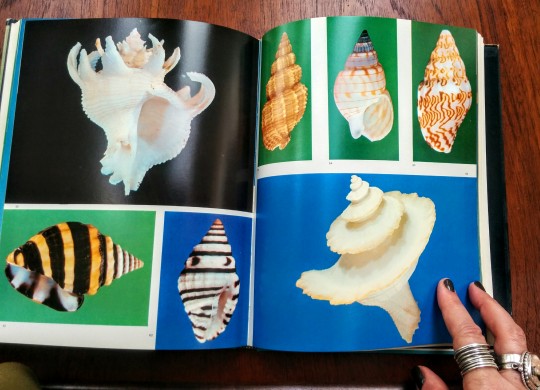

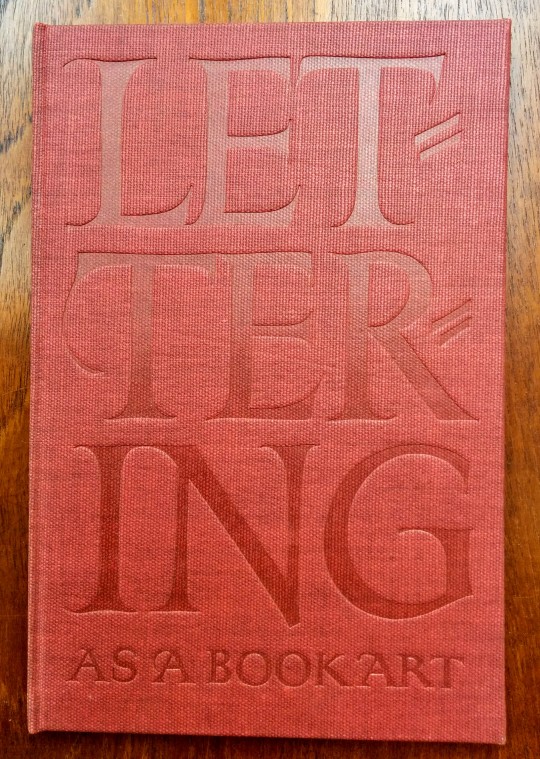

This is just a small survey of my father’s library. Books on type design, on Russian theatre, on sea shells, oversized atlases and surveys of Currier and Ives and Audubon prints. I am now their keeper.