It’s good to start the new year with projects, especially if those projects involve mooching around galleries and writing poems. Lately, I have been immersed in the world of Martin Creed, in preparation for a course I’m running at the Hayward on the occasion of their Creed retrospective, What’s the point of it? You can find a guest blog by me on the Southbank website:

http://blog.southbankcentre.co.uk/2014/02/04/poet-tamar-yoseloff-on-being-inspired-by-martin-creed/

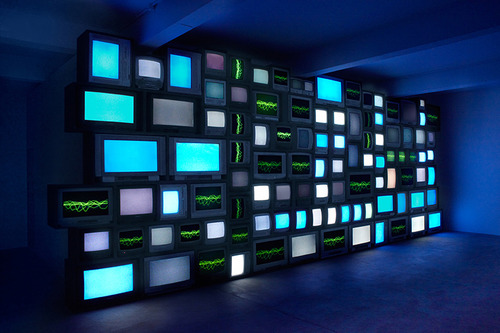

So much of Creed’s work is about chance and order, and the collision of those two conditions. So much of writing is a similar activity. When putting together the course (which starts on Monday and runs for five weeks), I wanted to think about basic themes and structures, but I didn’t want to be too determined about how things should be. I want to go a little crazy, move my students (and myself) out of the usual poetry comfort zone (sitting quietly at a desk with a pen and a notebook, waiting for inspiration to strike), because Creed’s work is often about discomfort – looking at things we think we shouldn’t really be looking at, things we suspect don’t really belong in a gallery, at least not in the hallowed spaces of the National Gallery, or on the pristine white walls of Mayfair. There is a defiance in the work, poking fun at convention, having a laugh. I’ve been having fun too, listening to sound poetry, reading lots of John Cage and Edwin Morgan, a bit of Carl Andre, fiendish Oulipo experiments where vowels are suppressed and lines lengthened by measurement. And wondering how all these grand and batty experiments might still alter what we do and how we do it. It feels a bit like limbering up before running a marathon (of course I’m thinking about Creed’s Work No 850, which involved runners sprinting through the galleries of Tate Britain).

At the same time, I’ve been commissioned by the poets Catherine Smith, Emer Gillespie and Abegail Morley, who have formed a group called Ekphrasis to look specifically at the relationship between poetry and art: http://www.ekphrasis.org.uk/. They are asking 13 poets in total to respond to the current Sensing Spaces exhibition at the Royal Academy. While not exactly as anarchic as Martin Creed’s show, the RA has commissioned six architects to come into the grand galleries of their Piccadilly building and let loose. The result is a show not simply of installations, but alternative spaces that (almost) make you forget you are in the RA.

But what I couldn’t forget while going through the show was that I needed to make a poem out of my experience, and that made me view the work differently, not just for its own merits, but also, and quite specifically, what could be mined from it? A quite mercenary approach to the gallery experience – one artist thinking what can I borrow, with impunity, from another artist (that is kind of the loose definition of ekphrasis, isn’t it)?

There was much I liked, but not much I thought I could use as a starting point for a poem. Not because the work wasn’t interesting, I just couldn’t see a way in for me. Something has to meet me on both an intellectual and emotional level (which takes me back to something Martin Creed has said, in negation to the idea that he is a chiefly a conceptual artist: ‘you can’t have ideas without feelings’). And then I walked into the space created by the Chinese architect Li Xiaodong. It is often difficult, sometimes impossible, to say why something moves you. Maybe that’s why you have to write the poem, to explore the question. But as soon as I passed through the simple curtain into Li Xiaodong’s construction of hazel twigs, forming a forest-like maze, which opens onto a shingle courtyard, I knew it was the installation I wanted to write about. Not that I knew what I wanted to say, of course – I’m still struggling with the poem itself – but that this was the place that could open my mind and heart to a poem.

I suspect I’ve quoted this before, a statement on the source of the poem by my great idol, the Irish poet Eavan Boland, but it’s so great, it’s worth saying again:

Explaining a poem is difficult. The method is inherently unreliable. There is too much instinct and error in the process to make its initiator a good witness afterwards. Akhmatova says of one stage in her poetry “my handwriting had changed and my voice sounded different.” But such clear beginnings are rare. The truth is that every poem has a different hinterland: a terrain of chance and shadow, of images in life which stay put until they become images in language.

I like that idea of the hinterland. Maybe that’s what the gallery is to a poet, a ‘terrain of chance and shadow’ that we enter, hoping to be charged up enough to make something new.