Occasionally people ask me about the derivation of the name of this blog. Regrettably, I can’t take credit – it’s the title of a poem by Wallace Stevens. When I first started, I posted a

statement on why I chose it:

In his poem ‘Invective Against Swans’, Stevens has a dig at those lovely birds, bringing them down a peg by calling them ‘ganders’ (which are actually male geese), dismissing their ‘bland motions’. I suspect Stevens had no serious gripe against swans; nor do I. They are decorative, they transform a landscape into a painting, they make me hum Tchaikovsky to myself. But stick them into a poem, specifically a contemporary poem, and they become a metaphor for all that is trite and precious. And that’s Stevens’ beef, all those ‘white feathers’ and ‘chilly chariots’. There he was, facing a newish century, a brave new world that had shaken itself out of a war; a new poet trying to find a new way of saying things. He is railing against the grandiose, the clichéd, the humourless. Never one to miss a joke: ‘gander’ is also colloquial in boon dock Florida for ‘a quick glance’, as in ‘get a gander of that’; also colloquial for the village simpleton, as idiotic as a goose. And as we’re talking specifically about a ‘male goose’, could the poet be referring back to himself, possibly to all his fellow bards (how close that is to ‘birds’!) as well?

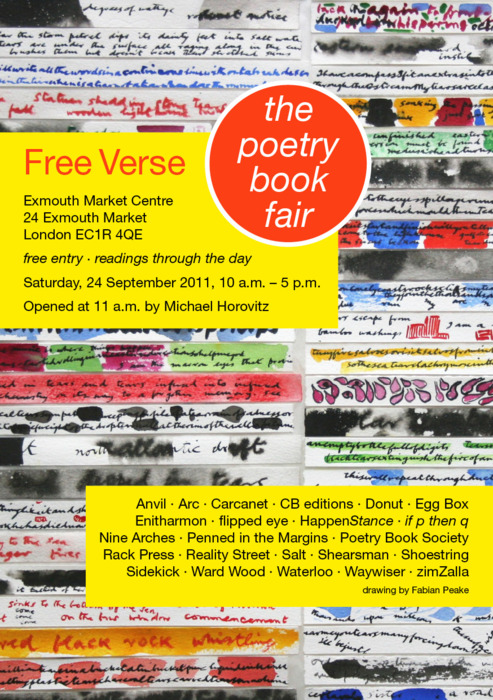

I suppose my aim in this blog has always been to explain my notion of what I find beautiful in the world, which is not always typical (swans being an easy measure of ‘typical beauty’). Stevens has been one of my guides. His work has made me interrogate image and language. When I was thinking what to call this collection of random thoughts, he seemed to provide the right phrase. I am not the only poet to reference Stevens in this way. One of my favourite contemporary presses is Shearsman, its name taken from a line in ‘The Man with the Blue Guitar’: ‘The man bent over his guitar / A shearsman of sorts.’ The musician becoming a maker (a shearsman being a cutter of cloth), as is the painter (Picasso) or the poet (Stevens). The poem is a manifesto for the making of art, and therefore the shearsman is an appropriate symbol for a press that espouses the made poem, an object that sometimes challenges convention, like Stevens, like Picasso.

I have recently discovered that an electronic duo based in Brussels have named themselves after one of my poems. Here is a link to Mannequins on 7th Street:

https://soundcloud.com/mannequinson7thstreet

On their site, they talk about the name as an ambient reference to the general chaos of city life, something they attempt to reflect in their music. Ironically, the poem came not from the place itself, but from a drawing by Anthony Eyton; so like the shearsman of Stevens’ poem, who presides over poet, painter and musician, the title Tony gave his drawing now radiates out over all of us.

It makes me think too of how some artists have the right name. Sometimes a name even becomes an adjective for an artist’s practice; to say a poem is Plathian is to say its images are dark and strange, its language clipped and sparse. Plath’s name is monosyllabic, it sounds like the noise that a pebble makes hitting the water. She loved the assonance of soft ‘a’s.

I have a name that is invented. The story, although intensely personal to me, is really a common one: my grandparents arrived at the port of Galveston, Texas, with their papers in Cyrillic and not a word of English. The desk clerk asked them to say their name aloud, and he took it down as he heard it. YO-SEL-OFF. As a poet, I value the strange name that no one can spell, that was made up on the spot, that makes me sound rare and exotic, the grandchild of Russian immigrants who went to a new country to make a new life. After all, we are always inventing ourselves, making up names for what we create.