Birthdays are always occasions to take stock of where a person is in life. On mine (one with a 9 at the end, which can only mean a milestone is a year away) I find myself in Middlesbrough, a city I seem to visit annually, at least over the last three years. Middlesbrough reminds me of Detroit – it wears its ruination like a moth-eaten evening gown. I remember last year arriving at the venue where I was about to do a reading; the sat nav informed me ‘you have arrived at your destination’ and before me was a scrubby bit of wasteland with a tethered horse. I was five minutes away from the main train station, in the centre of town, but ‘over the border’, the term for what I now know is the wilds of Middlesbrough (or as us Americans say, ‘the wrong side of the tracks’), once a dangerous and renegade part of town, but now attempting regeneration.

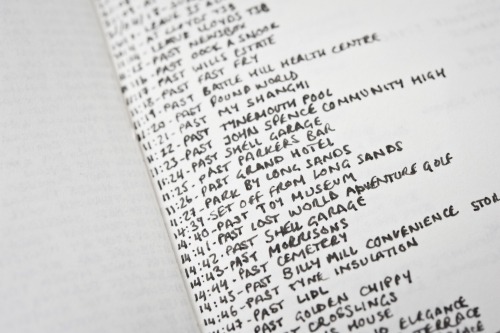

I started off at mima to see not only an amazing exhibition of later works by Louise Bourgeois, but also a group show of local artists entitled Chance Finds Us. The name, as you might imagine, references a ‘ritualised approach to making work’, to quote the curators Anna Vibeke Mou and Nick Kennedy (both of whom are included in the show), adopting chance operations as part of their practice. Many of the works are informed by travel. Rachael Clewlow’s diptych 133.52 Miles Walked, Key (Explorer 306/OL26) comprises one panel of densely-painted horizontal stripes, and another of spherical forms which extend like a DNA model over a grid. The works are linked: both chart a series of colour-coded walks around Middlesbrough in which the artist records a new location every minute (a notebook covered in minute handwriting lists the destinations) carefully written out in the ruled lines alongside each stripe in one canvas – each stripe, a different location, is assigned a new colour – in the other, shown as a mapped grid of discs in corresponding colours.

The attention to detail is painstaking and obsessive – it plots a journey not by a map (which has its own specific coloured codes) but by a rainbow of possibilities – why go on this journey and not another? How might you chart the movements of one person over a given period of time?

As if to attempt to answer those questions, I participated on a walk of Middlesbrough’s cultural landmarks led by the local poet p.a. morbid. Morbid was brought up in the city, and brings not only his personal marking of the changes in topography to bear, but a growing assemblage of history and image, both official and unofficial, of the way the city has altered in the last 200 years. Again, the comparison to Detroit is apt – Middlesbrough grew rich on shipping, had a peak in its fortunes in Victorian times, and experienced a dramatic shift in fate from the end of the second world war.

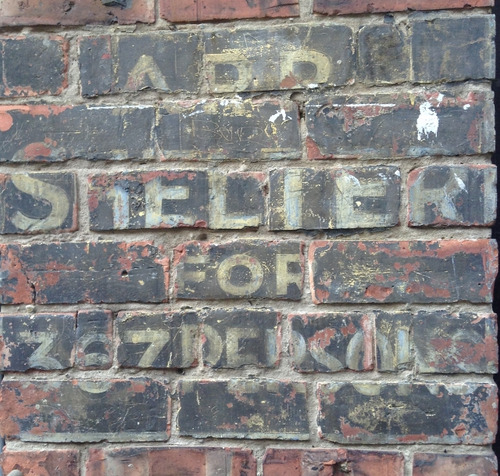

What Morbid showed us on the walk was not what is – the things we could see around us – but what has been, what might be again. Story after story involved destruction – by accidental fire, by council ‘improvements’, by a misguided sense of what would be appropriate at the time. He was armed with a collection of black and white images of extraordinary and grand Victorian structures that stood on the sites of ugly 60s and 70s office blocks. The grand city could still be glimpsed in the old Town Hall (still standing but empty and derelict), the Customs House, the Empire Theatre. A lesson in what should be cherished and protected in case it is lost.

As we walked, the mima show was still in my mind, especially the work of Nick Kennedy. His piece for the exhibition, Timecaster, presents a gathering of clear-domed discs, each encasing a piece of white paper, an exposed clock mechanism, with a silver lead attached to its moving second hand. As the hand revolves, it leaves an intricate spirographic pattern on the sheet – over the course of the exhibition the marks will grow darker and darker as the second hand makes its sweep.

It occurs to me that what time does is darken our mark (certainly with each birthday). This can be seen as a negative: the darker the mark, the more it loses its intricacy, its definition, until we are left with just a solid mass of black. But you might also say this is positive: the darker the mark, the more indelible. The more we repeat our stories of place and what happened there, the more they become ingrained in us.