Rip it up and start again

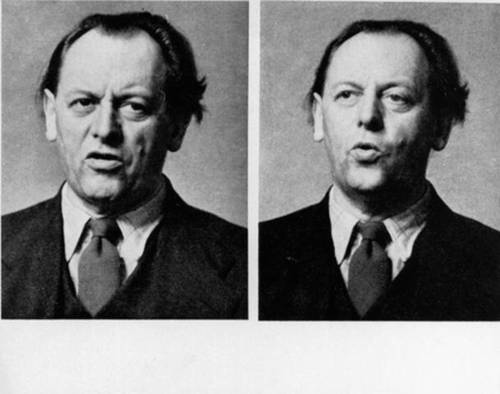

The German artist Kurt Schwitters arrived in Britain in 1940, after fleeing Germany, where he was labelled a degenerate artist by the Nazis, and then Norway, after the German invasion of that country. Schwitters’s practice was to make new things from the fragments of what had come before: refuse, found materials, abandoned scraps. To describe this work, he coined the term ‘Merz’:

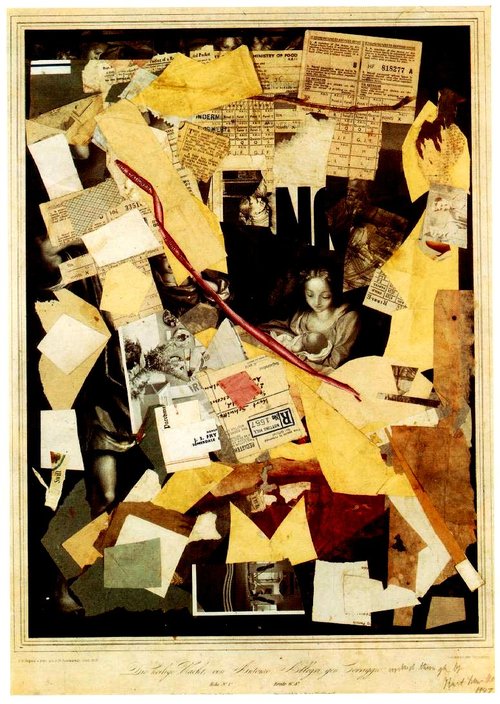

I call[ed] my new manner of working from the principle of using any material MERZ. That is the second syllable of Kommerz [commerce]. It originated from the Merzbild [Merzpicture], a picture in which the Word MERZ, cut out and glued-on from an advertisement for the KOMMERZ-UND PRIVATBANK [Commercial and Private Bank] could be read between abstract forms …

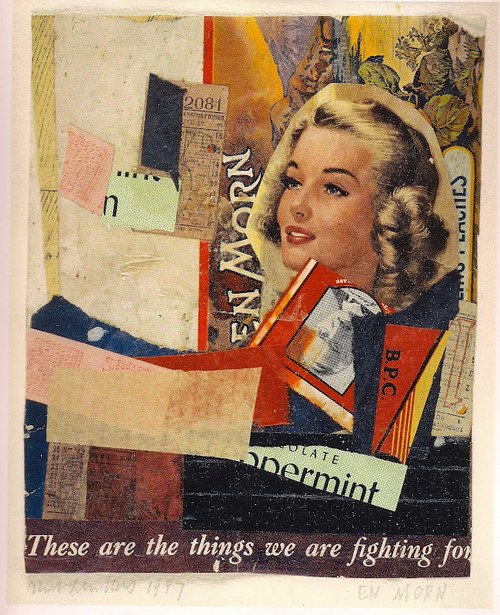

Schwitters was always interested in words, but not necessarily in their meaning. Like all of his Merz works, he liked to cut up words, reconstruct them, present them in fragments, so a glimpse of a phrase might catch your eye, divorced from the rest of the text around it. He liked the shapes of letters, and typography, so he could find pleasure in the simple grid of a bus ticket or the bright graphic of a candy wrapper. What strikes me about his collages is that they construct a narrative of his movement through Europe – some of them contain texts in German, Norwegian and English – so that they become emblematic of the urban experience, not just in their frantic energy, but in their mix of words: a kind of artistic melting pot.

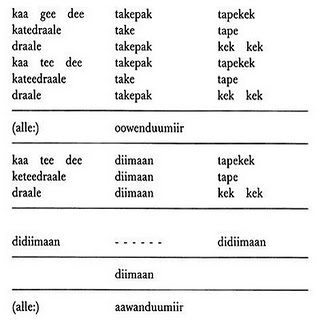

There are also his ‘sound poems’, which when viewed on the page look like Finnish on acid but are actually not a recognisable language (which made me wonder if the Icelandic band Sigur Rós had come across them when inventing the language of their lyrics). The greatest of these is the Ursonate, or sonate in urlauten ( which translates as ‘primordial sonata’ or ‘sonata in primordial sounds’). Schwitters left instructions for reciters of the 30-page work, mainly advising on the correct pronunciation of the letters. Perhaps the most important of these interpreters is the Dutch poet Jaap Blonk. But we also have recordings of Schwitters himself reciting the poem, sounding like a deranged exotic bird:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6X7E2i0KMqM

How to process the world he had known, the destruction of Europe through two catastrophic wars, the experience of being made homeless and turning up in a foreign country, grappling with an unfamiliar language, always being alien (for even in Germany, he was different)? Perhaps the Ursonate is the only acceptable response – the world is nonsense, impossible to fathom. We just have to make sense of it as we can. And, to paraphrase Eliot, we must shore our gathered fragments against ruin.

Schwitters ended up in rural Cumbria, creating a Merzbarn (he would have liked the fact that after his death, part of it was lifted away and transported to Newcastle – a very Schwitters-like intervention). But he also painted conventional landscapes and portraits to earn a living – these are completely ordinary, boring even, without a hint of the concerns of the more radical artist and thinker. In that respect, perhaps he did understand what he had to do to settle in and become one with the English. A collage work created in this period is interesting in that it is one of the few in which the text is meant to be read and understood: these are the things we are fighting for.

The Ursonate in full here: http://www.costis.org/x/schwitters/ursonate.htm

Schwitters in Britain is at the Tate until 12th May: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/schwitters-britain?gclid=CJrd7tzRu7UCFabLtAodEFoAuA