As I walked through the galleries at Tate St Ives on a sultry Friday evening last week (beginning in a room of stunning Gabo constructions) it seemed to me that the artists assembled were concerned in various ways with measurement: of distances, of shapes and forms, of human scale, of volume and air, of experience.

How does a person walk through an enclosed space, from one end of a room to another? It’s just something you do, naturally, instinctively, one foot in front of the other, without thinking about it. In Martin Creed’s installation, Half the air in a given space, he has filled half the volume of the Tate’s curved gallery with white balloons, like cartoon clouds. The visitor is invited to move through them; it was surprising how resilient, how hard they were, every now and then, one yielding to enough pressure to burst. You had to fight your way through a solid, rubbery mass, your steps slowed, as you poked and kicked them into submission – the brilliant plot of some demented clown. When I was finally released at the other end of the gallery through a glass door, one or two balloons escaping in my wake, I smelled of rubber, like something slick and strange and my hair was standing on end. But what I thought of was breath, the breath of a person walking, the breath of effort, the breathlessness of blowing up thousands and thousands of balloons (ok, I concede they would have used a machine for that). Charles Olson said that a poem represents certain laws and possibilities of breath, of the breathing of the man who writes as well as his listenings. In the gallery, muffled by those rubber cushions, all I could hear was the sound of myself breathing (as well as the sounds of fellow balloon-strugglers laughing and trying to find each other in the depths).

The gallery above contained Lucio Fontana’s canvases and structures, slashed and shot full of holes, as if the artist was hell-bent on destroying whatever perfection he might create— although Fontana did not consider his holes, his interruptions, to be a form of destruction. A hole is an intervention, something which disrupts, but not necessarily in a negative way. You want to touch it, to stick your finger in it. It suggests the hand of the artist, a bit of a joker, winking at the viewer. But the hole has (excuse the pun) deeper connotations. Jeanette Winterson, writing about Barbara Hepworth, said

Holes are also tunnels or worm-holes making a route through time … The hole is a way back and a way forward. The hole is also the space occupied by the air we are breathing now, by the sunlight that has taken eight minutes to reach us, and by the starlight that is two thousand years old. In the space inside, or rather through, the sculpture, time is both present and meaningless – and that is time’s true nature, it does and it does not exist …

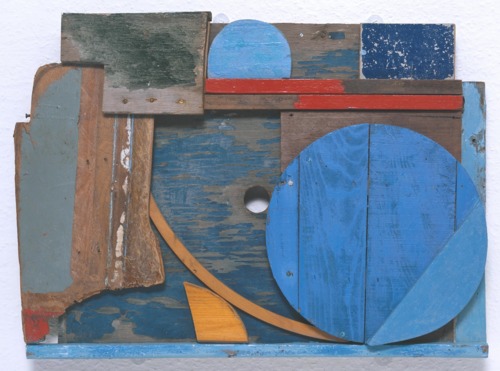

Moving away from Fontana, I found myself in a room full of Margaret Mellis’s driftwood constructions; another way of looking at proportions, associations. Mellis trawled the shore for pieces of wood – the remains of larger structures; dissembled, worthless – and by bringing them together made something new. That’s what poets do too – find connections in what is seemingly random. So I was particularly pleased to hear Telfer Stokes, Mellis’s son, quote her as saying that when she was able to make such connections, to see how a construction might come together, it was like reading a really good poem. Each construction is like a window framing multiple landscapes; the landscape of the beach where Mellis found the constituent parts, the landscape of the boat or crate or tool that once was whole (now ‘hole’), the new landscape she’s made from such simple means, and which means more than the sum of its parts. It is hard to say why they are so beautiful, so complex and compelling; maybe it has to do with all the hands that went into making things, things which were destroyed then constructed anew.

And to move from Mellis’s constructions to Agnes Martin’s bands of soft colour – almost non-colour; just shade, tone, light – on canvas made perfect sense. As Martin said, like crossing an empty beach to look at the ocean. And there it was, outside the gallery, just waiting for us …

http://www.tate.org.uk/stives/

The title of this post comes from an installation by Roman Ondák, which invites visitors to have their height measured and recorded on the gallery wall:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BNiwsDnzFiw

The show Margaret Mellis – Structure and Colour is also showing at the Wills Lane Gallery during the Tate Summer season: www.willslanegallery.co.uk