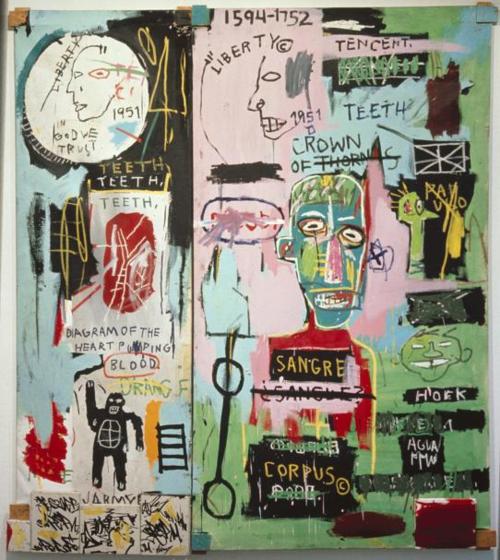

Well, not exactly the sea – but a view of the dreary Mersey, like a slab of wet concrete, through the window of Tate Liverpool. But we find the sea inside, contained in vast canvases by Turner and Twombly, turbulent, swelled by storm; the manifestation of the Sublime, as Ruskin defined it, a perilous beauty inherent in what is dangerous, terrifying.

The sea is contained inside us as well; Ruskin talks of ‘the effect of greatness upon feelings’. Both Turner and Twombly depicted the story of Hero and Leander, star-crossed, storm-tossed lovers, as a illustration of the Sublime. In Turner’s painting, the towers of Abydos fade in the twilight gloom, while the Hellespont gleams under a crescent of moon; its glow is casts long corridor to Sestos on the opposite shore, which is not visible, but we know that Hero is there, waiting (we also know that Leander will drown trying to cross the sea to her, and when Hero discovers her lover is dead, will throw herself from her tower into the sea to join him). To the right, there are nymphs or angels emerging from the water, almost water themselves – ghostly in the dim light. I don’t know if Turner would have known Keats’s poem on a Leander gem, where he evokes ‘sweet maidens … with a chastened light / Hid in the fringes of your eyelids white’, for whom Leander is ‘a victim of your beauty bright’, but Keats could be speaking directly about Turner’s extraordinary light effects, and Turner could be realising Keats’s maidens in paint.

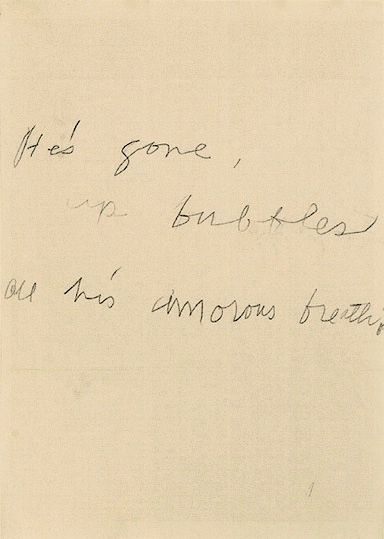

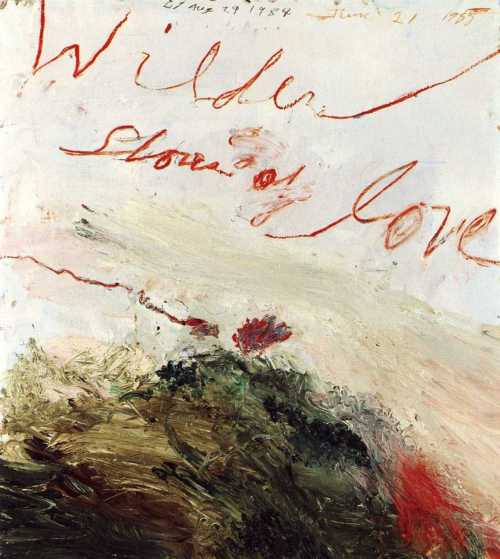

Twombly knew Turner’s painting, he knew Keats’s poem. The first panel of his quadriptych shows Leandro being tossed in the sea, a manifestations of his churning passion; the next two panels show the sea overtaking and erasing his passion, his presence – the triumph of nature over man (and of the processes of nature over human emotion), until the final panel leaves us with nothing, apart from the final line of Keats’s poem: he’s gone, up bubbles all his amorous breath. A very Twomblyesque notion – there is nothing that remains of our passion and fury once we are silence and ash. Just words, paintings.

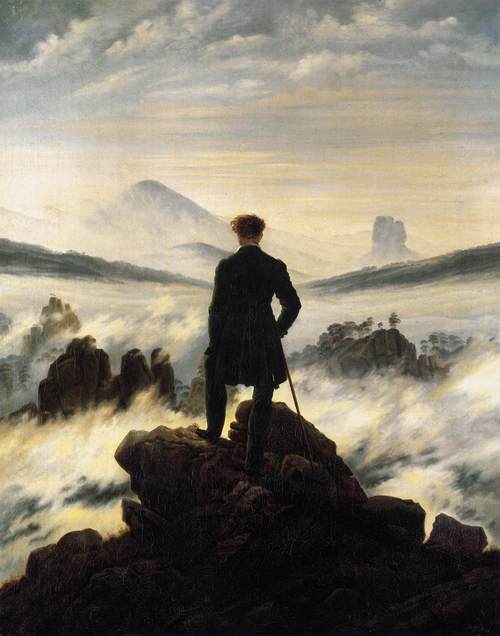

Twombly said ‘painting is a fusing of ideas, fusing of feelings, fusing projected on atmosphere’, his take on the Sublime perhaps. That makes me think of Turner’s contemporary,Caspar David Friedrich, and his painting Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer (not the actual sea, but a sea of fog, a haze of confusion and doubt).

I think of Byron swimming the Hellespont in honour of Leander, which makes me think of the Louis Edouard Fournier painting of Byron attending the funeral of Shelley, drowned in 1822 (which we had just seen the same morning in the Walker Art Gallery).

Shelley is buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome with Keats, who died the year before him; and Keats’s epitaph reads: Here lies one whose name was writ in water.