Today I’m a guest on Lynne Rees’s blog The Hungry Writer: http://tinyurl.com/45xg9fk

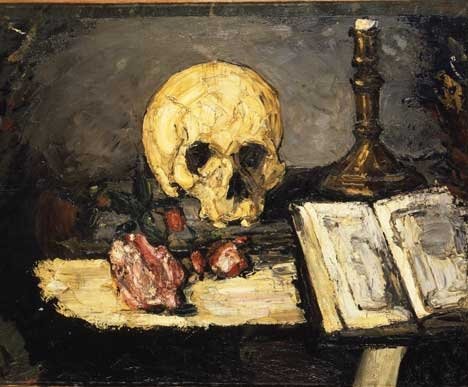

Cezanne

Dark Blue Square

St Ives remains with me even now I’ve returned to the urban hub of Stockwell – the hard beauty of the landscape matched by the clarity of the artists who depicted it. So with the landscape still very present, I was saddened to read of the passing on Sunday of Breon O’Casey, one of the last of the generation of St Ives artists apprenticed to Hepworth at Trewyn. It is of particular interest to me that O’Casey came from a literary background – his father was the playwright Sean O’Casey, a contemporary of Yeats. It is perhaps too easy then to say that his paintings have the feeling of small moments arrested in time: birds captured mid-flight, landscapes reduced to the elemental (a field in spring, a group of circles resembling a cairn or pagan stones, a constellation suspended in a night time sky). There is the exuberance of the French painters he loved, Braque and Matisse, but in the restrained and earthy palette of the Penwith School.

It was only a few months ago that I went to a show of his work at Somerset House. I didn’t actually know it was on; I’d just come from the Courtauld where there was a show of Cezanne’s sketches for The Card Players (an interesting transition, as it happens). It was a bleak winter day, flat grey and featureless; the sort of day you get in London in January and February, when one day blends into the next and seems to go on forever, and you are just waiting for a small sign of spring. And O’Casey cheered me, with his simple birds and flat squares of pure colour – the sort of painting that looks simple enough (well, maybe to those who can’t paint) but which is pared down and spare and studied, like a poem by Charles Simic. Difficult to accomplish without being twee or shallow. But O’Casey’s work is resonant, meaningful.

Take for example this painting, one of his many stylised depictions of birds, the title of which is Dark Blue Square. In that title there is a statement about proportion, measurement; I think of the way the sky is viewed from the ground, slivered between buildings or trees. It is a portion of sky, like the painter’s own patch. But then it appears in the bottom left of the picture, not at the top as we’d expect, so maybe our bird is swooping over a lake or reservoir. There is a paler shade of blue just touching its body – a shadow, a memory of light. The two brown columns that hold it are like tree trunks, or legs. A simple juxtaposition of shapes and colours, the colours simplified to brown, white, blue. But it’s the blue O’Casey wants us to focus on, bright and vital against the dark brown, the bird just passing through.

It’s like the last soldiers of the Great War, all those artists of that generation passing. They brought us modernism, which might feel like old hat now, but they were pioneers then (with Hepworth cracking the whip). And the work still feels valid and exciting.

Nature morte

On the cover of Paul Muldoon’s most recent collection, Maggot, is a photograph of a dead bird. The bird is not pretty or peaceful in death, like those Victorian depictions of Cock Robin (thinking particularly of the amazing tableaux created by the taxidermist Walter Potter for his Museum of Curiosities). The bird is in the process of decomposition, and we can see through its feathers and flesh, straight to its bones, the contents of its stomach – the plastic detritus of beaches and garbage dumps which probably aided its death. The bird is a dull brown (apart from the brightly-coloured plastic exposed once again to the elements) to match the earth it lies on; eventually it will merge with the earth. The earth is as parched and dead as the bird.

They say you can’t judge a book by its cover, but the poems in this book are about the body in its slow crawl to disintegration. In an interview in the Economist, where it was suggested that the subject matter explores the ‘grotesque’, Muldoon said:

I don’t know where the grotesque begins and ends. It first refers, as you know, to paintings seen in grottoes or the basements of ancient buildings in which there were murals that represented animals and human figures that were seen as being somehow distorted or exaggerated. I think the business of making metaphors almost inevitably involves distortion or exaggeration. My love is like a red red rose only in a very specific sense. I tend to see the canker in the rose, I guess, which may account for your sense of the grotesque. A grotesque is also a term for a clown or a fool and there’s a lot of clowning in these poems. A lot of acting the maggot, as we describe acting the buffoon. The clown’s face is a death mask, I suppose.

But my purpose is not to discuss Muldoon’s book, as many critics have done that already, really more to think why death continues to be so attractive a subject for poets, as it has been for many years (reading Muldoon’s recent poems took me back to Marvell’s ‘To his Coy Mistress’ and Donne’s ‘The Funerall’, those dead poets we still carry with us as living poets). The most obvious reason must be the inevitable truth of death; the poet’s need to explore the notion of his/her own mortality (not to mention the desire to leave something of oneself for posterity, even if what you leave behind is a few slim volumes).

But there is more to it than that. Poets like to get below the surface of things, to dig deep, and once you’ve described the sweet soft flesh of a lover, it is only natural to want to get under the skin; so that the poet is a kind of maggot too, not just in the sense of the clown as Muldoon has suggested, but as a seeker of deeper meanings. Poets are parasitical, in that they steal from each other, feeding off those poets of the past that they love, but also feeding off their loved ones for their stories and their emotions. Anything for a good poem.

Also, a lot of poets live in a continual state of greyness. By that I mean they (and here, as throughout, I really mean ‘I’) see both sides of every situation, and often there is a chink of blackness within the light. But that doesn’t mean they are depressing, just realistic. There is not a lot of joy in our current world, and any joy we make comes from human contact and communication. As Muldoon reminds us, the rose will wither and die. The point is that it is beautiful for a moment. The moment is important, but so is what comes after.

In my recent reading of nature poems for my upcoming workshops, I have been struck by the amount of ‘dead nature’ I’ve encountered. Perhaps a chance for the poet to view up close a creature that was in life too fast to capture. Perhaps an opportunity for comparison as well as reflection. Muldoon reminds us, after all, that the poet is in the business of making metaphors. Death presents us with a way of saying a few final words on what finality really means.

More dead birds, and other creatures here, courtesy of poet Karen McCarthy Woolf, whose poem ‘Wing’ was featured in the Winter issue of Poetry Review : http://opennotebooks.co.uk/2011/01/wing-takes-flight/

Full Muldoon interview here:

http://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2010/10/new_poetry

Image is Cezanne’s Nature Morte, 1866-67