Various discussions over the past week have triggered a preoccupation with the concept of home. As readers of Invective already know, I have made my home in London for the past 26 years, having spent the previous 21 years in New Jersey and New York. When I first moved here – with no particular plans, and probably no clear intention to stay – I found I was writing poems about my childhood in America, as it seemed I had gained the necessary distant to do so, not just physical distance, but also mental distance. At a certain point, when I started to establish a life for myself here, those American poems stopped. If it can be said that the majority of my poems are situated anywhere, it is London, or at least an urban location resembling or based on London. In my favourite poem by Cavafy, he talks about the possibility of ‘finding another city better than this one’ but the reality is that:

This city will always pursue you. You will walk

the same streets, grow old in the same neighborhoods,

will turn gray in these same houses.

You will always end up in this city.

Cavafy’s poem is relentlessly negative, concluding ‘As you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner, / you’ve destroyed it everywhere else in the world.’ So the city becomes a metaphor for his failure, which he is fated to carry with him forever. Although I would contest his conclusion, I agree with Cavafy that a place you have spent much of your life becomes engrained in you, and any other place you visit is held against that dominant place, the place you call ‘home’. You do carry your city with you everywhere you go, like a garment you wear against your skin. But for me, that is a comfort rather than a burden.

‘Home’ is necessarily complicated for me, in that I consider London home, but I also recognise that I am not a Londoner. This is my adopted city, and perhaps for that reason, it is always precious, and I have never taken it for granted. If you think of writers like Conrad or Kundera or Nabokov, it is their otherness, the fact that they were from one place, and made a decision to reside permanently in another (and give up their mother tongue to write in the language of the place they made home) that charges their prose with a quality of surprise and energy. I have just switched from one kind of English to another (sometimes mixing my poems with both American English and British English, as I do in my speech). I think of myself as Anglo-American, and, like Plath or Eliot (if I could even begin to compare myself to them) my poems reflect the dual nature of who I am.

At the recent Place: Roots – Journeying Home weekend at Snape Maltings, the discussions began with Benjamin Britten and his commitment to place (in his case, Suffolk) in his music. The beginning of Peter Grimes just sounds like the beach at Aldeburgh; it makes sense of the place entirely, so that no other music can represent it so well. This idea of being firmly rooted was carried through to a discussion by Patrick Wright of the German writer Uwe Johnson, who, like Sebald and Hamburger, ended up in eastern England (Johnson rolled up in Sheerness, which even he thought was a dump, but somehow that awful place added a quality of stark alienation in his writing).

Wright made the point that ‘roots are also routes’, which makes me think of writers such as Bishop who was always searching for a home, and laid down roots in many places, only to uproot herself and start again. I always think of her line (in Questions of Travel) ‘Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?’ every time I embark on a journey elsewhere, impossible as it is to take away with you the ‘folded sunset’. It seems that lately I have returned to America, not physically (I have only been back once in the last six years), but psychically. When doing readings from The City with Horns in 2011, I found myself telling audiences that the New York I depict in my Jackson Pollock poems isn’t the New York I remember, but the New York of my parents’ generation, a New York that filled my early years with stories of glamorous book launches and classic cocktails. And now I am trying to recreate the New Jersey suburbs of the 70s in my novel – thinking of Cheever, and Rick Moody, and Tony Soprano, and my own childhood.

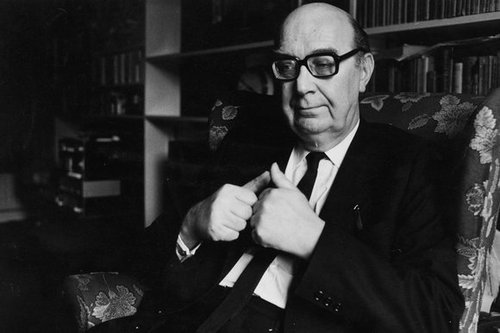

I’ll finish on this poem by Larkin, which Anne Berkeley and I were discussing during the Snape weekend – the definitive statement on home:

Home is so sad. It stays as it was left,

Shaped to the comfort of the last to go

As if to win them back. Instead, bereft

Of anyone to please, it withers so,

Having no heart to put aside the theft

And turn again to what it started as,

A joyous shot at how things ought to be,

Long fallen wide. You can see how it was:

Look at the pictures and the cutlery.

The music in the piano stool. That vase.