A funny thing, memory. The mind plays tricks, gives you back a replica of what was really there. But of course, what was there is not what is here; places, situations, people do not remain static. Only in memory, and over time, even memory becomes unreliable.

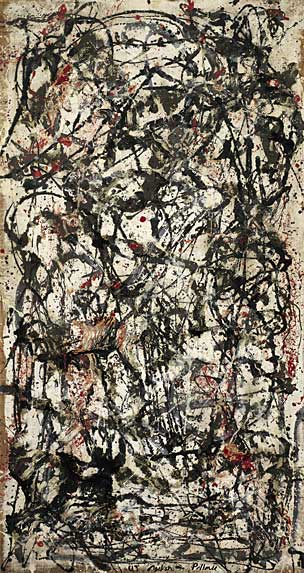

Back in Venice, I return to the Guggenheim, my first visit since I wrote about Jackson Pollock’s great painting Alchemy. The painting is darker than I’d remembered, larger. I found it oddly comforting the last time I saw it, but this time it is frightening as well. Vast and impenetrable. The image in my poem that conjures ‘a man stranded in space’ feels accurate. But it’s another Pollock that catches me this time: Enchanted Forest. Alchemy is a landscape, the sky at night swirling with galaxies, but Enchanted Forest is vertical, human-scale, like a door you could walk through. But, if you could walk into the painting, you would be immediately barred by the thick tangle of … branches? Thorns? Entry is impossible. The twisting mass of black is interrupted by flecks of red, like blood, just to enforce the idea that this is not a forest for mortals.

In another room, Joseph Cornell’s Setting for a Fairy Tale. A classical façade in the foreground, but clearly two-dimensional, like a stage set. What is behind is dense forest, real branches resembling trees looming over the house. The branches are painted silver; ghostly, but somehow they are more real than the cut-out mansion, the play house that they frame. The windows in the house are actually mirrors; another illusion. The whole construction is behind glass, boxed, framed. It’s only when you stand back from it do you notice the tiny figures in the foreground, almost blending into the façade. The mansion is a wall which will prevent them from entering the forest behind, as it has no proper doors or windows. The branches arch over the flimsy façade, as if they might break the glass and escape the box. For me, it has the same effect as Enchanted Forest, but on a miniature scale. The trees, the real three-dimensional trees, shrunk to fit their box, suggest that this fairy tale is grim(m). There could never be a happy ending.

And in another room, Arthur Duff’s Black Stars. Strands of vertical rope, like the kind of rope you see on boats along the canals, but not quite so thick; black, and knotted at intervals, so when you stand back, there is a dense cluster of knots at its centre. Like both the Pollock and the Cornell, Duff is playing with dimensionality. From a distance, the rope looks like a flattened surface, just paint on a canvas; it’s only when you approach do you realise. Are the stars knotty problems for us to understand (like alchemic equations)? Is this what we might call ‘dark matter’? Are we so small in the great scheme of things? Are we so easy to fool with simple tricks of perspective that any magician could perform? Do we find we get tied up in knots when we seek explanations? Is memory a dark clot in the brain, a thick tangle of trees we can’t penetrate?

Outside, the cold winter light of the canal.