It is overwhelming, often overblown, sometimes infuriating, but it is still London’s great annual art event, and always worth the effort of struggling through the crowds. There were many things I loved at this year’s Frieze, but for the purposes of this post, I will concentrate on works that referenced notions of the book.

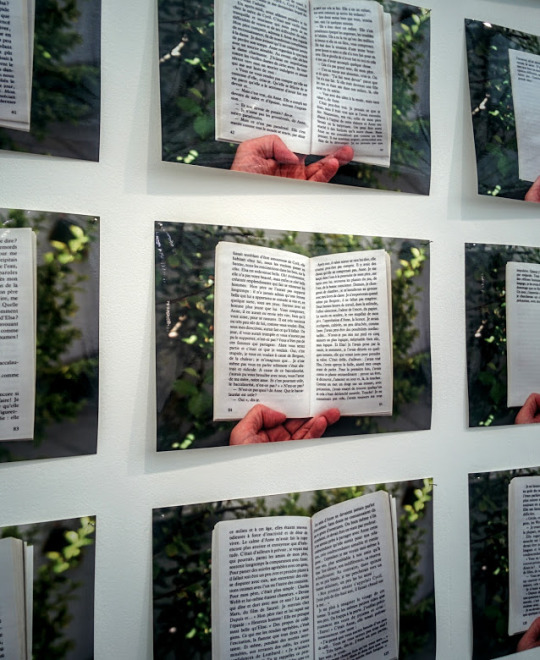

To begin in the main fair. I’ve seen the work of Hans-Peter Feldman before, and admired his playful take on collecting and grouping – sometimes to the point of obsession, perhaps in an effort to achieve completion, or at least to impose order in chaos. The Barbara Wien gallery presented his piece ‘Françoise Sagan, “Bonjour Tristesse”’, a series of colour photos pinned casually to one wall of the display, depicting the disembodied hand of a ‘reader’ holding up Sagan’s book. The reader is outdoors – there is a bush behind him (it looks like a man’s hand) and sunlight catching the green leaves. Each photograph shows a double-page spread, and with the time and inclination, a viewer could read the entire book, although perhaps Feldman’s goal is to invite us to consider the simple pleasure of reading a book (a sad book at that, about the blossoming and disappointment of a teenage girl) en plein air. Perhaps too, Feldman is interested in the book itself – its materiality, the presentation of text and language, the paper (presenting one paper medium through another paper medium).

The Belgian artist Hans Op de Beeck is interested in art as stage set. In addition to his installation work, he makes sculpture and film that pitch the viewer into fantastic worlds, often quite dark. But his installation for the Marianne Boesky Gallery, ‘The Silent Library’, is pure white; once you step inside you are surrounded by clean, empty, clinical spaces. There are shelves, furniture, amazing tableaux on the console tables of birds surrounded by fruit and plants (still lives of still lives) – all white. Even a white ashtray with white cigarette butts. The spines of all the books are white, and so any notions of meaning or language are rendered impossible. It recalls grand libraries in stately homes where the leather-bound volumes were not so much there to be read, but to provide a kind of insulation from the outside world. But I was also reminded of the pure white rooms of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the notion that there is something alien, slightly threatening about such whiteness. Joan Mitchell, who hated white, said: ‘It’s death. It’s hospitals. It’s my terrible nurses. You can add in Melville, ‘Moby Dick’ a chapter on white. White is absolute horror. It is just the worst.’

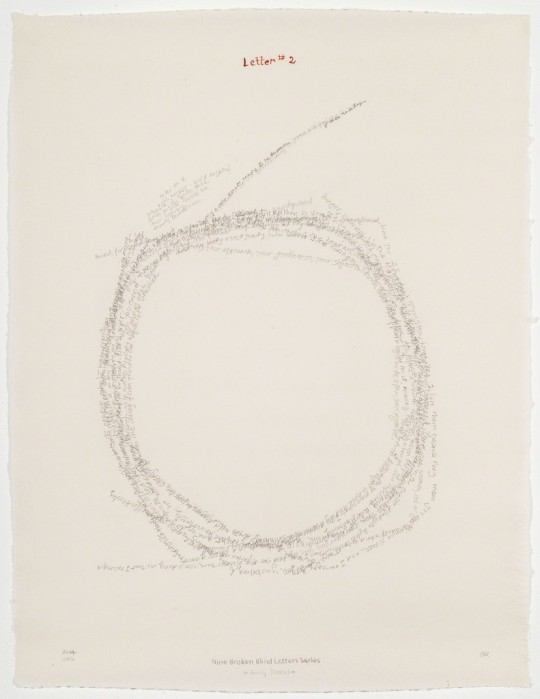

At Travesía Cuatro’s stand, Spanish artist Elena del Rivero’s delicate set of pencil drawings on handmade paper presented a series of ‘letters’, incorporating borrowed texts from writers. Her interpretation of Emily Dickinson renders her words as spidery handwriting, forming a circle – words that bend over on themselves, like voices speaking at the same time. A circle is also a continuum, a wreath, a ring, an opened mouth. By calling these drawings ‘letters’, del Rivero is addressing her chosen authors as well, giving their words back to them in another guise. The lightness of the mark on the paper is like a whisper – and so the drawings are like diary entries, very intimate, very personal.

Over at Frieze Masters, there were works by Ed Ruscha – Gagosian created an entire wall of his books and text pieces, winks and nods towards plainspeaking America. At Timothy Taylor there were destroyed books by John Latham – beautiful, like the ruins of some great library (in the wake of the wholesale destruction of ancient monuments, I see his work in a new light).

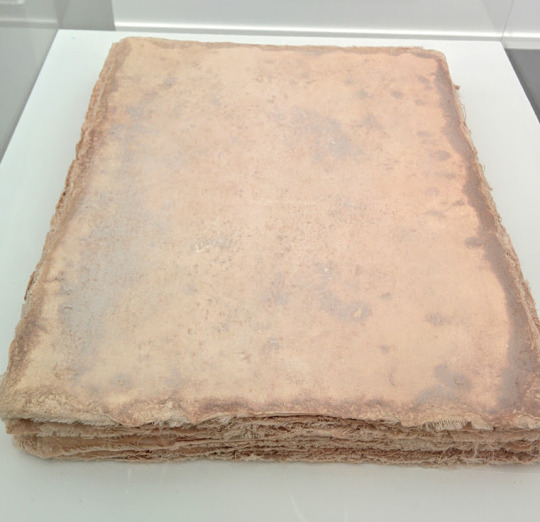

But a new discovery this year was the American artist Michelle Stuart, connected to the Land art movement of the 60s and 70s. Parafin presented her ‘ledgers’, sculptural ‘book’ works that contain objects from specific locations. Her ‘Bat Palace Book’ seals earth and feathers from Tikal, the Mayan ruins preserved in the Guatemalan rainforest. The book itself feels like an ancient object recovered from the site, its weathered pages like wrinkled skin. I found her books very moving. Even closed and behind glass, it felt like their pages held great secrets waiting to be revealed.